Department of Speech and Hearing Science rose from a humble start

BY BRUCE ADAMS

As humble beginnings go, it would be difficult to top that of the Department of Speech and Hearing Science at the University of Illinois.

In 1938, Dr. Severina E. Nelson repurposed a closet in Lincoln Hall to start an outreach program providing speech therapy. She began by assisting a student with some articulation difficulties. Sharing an office with colleagues and unable to find a private room, Nelson said, "Finally, the janitor volunteered to donate his mop closet so that I could set up a speech therapy lab. He moved to the basement."

If that were all there was to it, Nelson would go down in campus history as one of the more determined, innovative, and resourceful professors at Illinois and as a founder of what, in 1973, became the Department of Speech and Hearing Science (SHS).

But there is more to Severina Nelson, and SHS, than that.

“Nowadays, our culture is notoriously rough on the dedicated person with a cause, especially a woman,” wrote a group of students to Nelson upon her retirement in 1964. “It is true that all new concepts only get recognition after someone has spent years being persistent and farsighted until finally, the disbelievers are made uncomfortable and become believers. You’ve been a woman with a gleam in your eye, and thank heaven, you never became a casualty of our system.”

Nelson earned her B.S. in 1918 and her M.A. in 1923 in English at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She began her professional life as a high school teacher in Iowa, coming back to Urbana-Champaign in 1920 as an associate instructor in the Division of Public Speaking in the Department of English. After earning her M.A. degree, she pursued a career teaching interpretive speech. She was an engaging speaker, giving countless readings for campus groups, on tours across Illinois, and on radio shows. This led to her co-authoring a best-selling speech textbook with Charles H. Woolbert in 1927: The Art of Interpretive Speech (with a fourth edition still in press in the 1960s).

In 1932, Nelson was elected president of Sigma Delta Phi, a national honorary women’s dramatic and speaking fraternity. Fittingly, it was Nelson who introduced aviator Amelia Earhart during her March 21, 1935 appearance on campus—two years before Earhart’s disappearance. Nelson had built a profile as a director of dramatic productions, including those for the Women’s League, the annual Homecoming “Stunt Show,” and the Hillel Players.

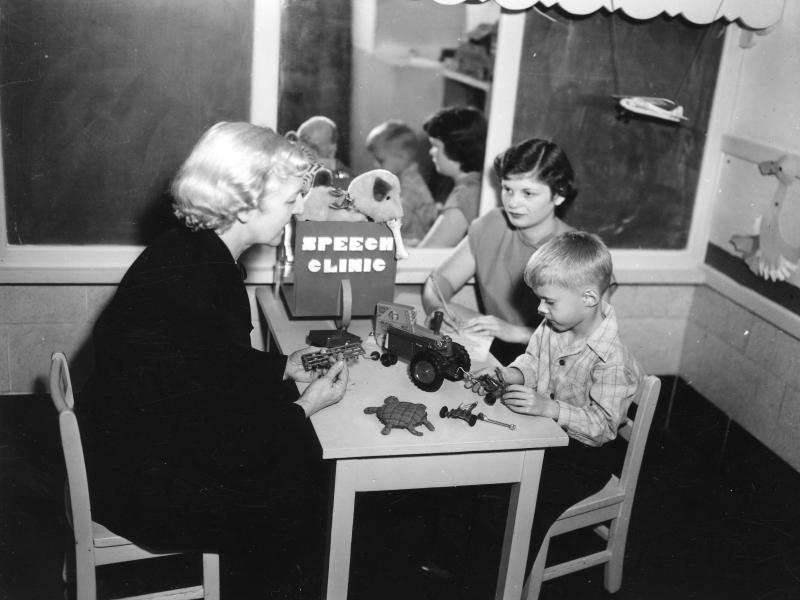

Nelson earned her Ph.D. in 1938 in Speech Pathology at the University of Wisconsin in Madison and then did post-doctoral work at the New York Medical College. The work Nelson began by helping college students with speech difficulties received funding and was then extended to community members. In 1938, she brought clinical practice at the University of Illinois into existence by establishing its speech clinic, serving as its director from 1939-59 and as a professor of speech from 1941-64. Some of Nelson’s early research in speech disorders focused on stuttering. She published three seminal articles from 1939-45 in the Quarterly Journal of Speech and The Journal of Pediatrics, on the role of heredity in stuttering, and in the Journal of Speech Disorders, on stuttering in twin types.

In 1939, the Daily Illini described Nelson as “one of the most popular instructors in summer school,” noting that “her office is different from the usual. Here you open the door and find yourself looking into a full-length mirror. Vanity isn't the reason for the mirror's being there. She finds it very useful in her speech correction work. Just during the past year, the speech department has made great advances in this work, and much of it has been under Miss Nelson's supervision. Patients are studied and classified according to their type of speech defect, then they are turned over to students in speech correction classes for help.” (Please see Editor’s Note below regarding terminology use in historical records) Most of the student therapists were women whom Nelson supported as the faculty advisor to the campus chapter of Zeta Phi Eta, the national women’s speech sorority.

By 1940, Nelson had secured a $2,000 grant to support her clinic and extensive office and clinical space in Gregory Hall, where individuals with cerebral palsy, hearing disabilities, and cleft palate received therapy. She also had established an educational program in speech therapy at the University of Illinois, with four years of undergraduate coursework and one year of graduate study. From 1943-1944, as the chair of a state legislative committee, Nelson delivered 50 to 75 speeches throughout Illinois to win passage of the committee’s bill to provide supplemental funds for local clinical efforts. With the onset of the World War II, veterans were returning with “organic and psychological disabilities.” The clinic’s funding from the farsighted bills in the Illinois legislature was augmented by federal assistance to veterans. Twenty-seven nationwide colleges and universities received this funding, notably clustered in the Midwest around the University of Illinois, including Indiana University, Northwestern University, the University of Michigan, and several branches of what would become the University of Wisconsin system.

The demand for speech and hearing specialists was such that Nelson wrote to her department head in 1945 that the University of Illinois Speech and Hearing Clinic was competing against Army and Navy hospitals to recruit therapists for work in the Champaign and Urbana school districts. By 1946, there had been 16 master's theses recorded in Speech and Hearing Science.

In 1950, under Nelson’s leadership and advocacy the clinic moved to the Lorado Taft House on campus (though, as she wrote in a letter, Nelson was convinced the University planned to demolish the building.) The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that “her enthusiasm, plus a brisk business-like air, are reflected in the rest of her efficient and enthusiastic staff.” A newsletter describing “Dr. Severina Nelson’s informative, vivid, and impressive account of the Illinois Speech Clinic” to the Urbana Rotary Club in January 1955 noted that “Professor Nelson filled her talk with case histories … all interesting. Urbana Rotary played a large part in sparking the state’s program—a program which for some years has been one of the best in the Union.”

When Nelson stepped down as director of the speech clinic in 1959, it had 10 full-time therapists. She resumed full-time teaching in speech pathology and oral interpretation, and by then, had advised more than 125 graduate theses. With her national renown, she was often requested as a speaker by groups and organizations across the country. After retiring in 1964, Nelson moved to Dallas and in 1978, received Honors of the Association from the Illinois Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Contributor: Cynthia Johnson Parsons

Editor's Note: As in many fields, perspectives and terminology in speech and hearing science (also called communication sciences and disorders) have evolved over the years, away from those appearing early in the historical record. For example, our focus has shifted away from correcting a person’s speech defects toward improving the intelligibility of their speech and enhancing the effectiveness of their communication with others.